Le 16 février 2019 a lieu, à Melbourne, en Australie, un hommage à Judith Rodriguez, poète dont l’influence se mesure déjà au nombre des jeunes poètes qu’elle a soutenus et accompagnés, et qui y témoigneront leur attachement à cette figure de proue qu’elle était à sa façon, toujours en première ligne de tous les combats (elle a représenté pendant de très longues années le Penclub international d’Australie, par exemple) : militant pour la culture populaire, la défense de la culture aborigène, les droits des femmes, la défense des immigrés et de ces clandestins arrivés par mer et rejetés dont elle parle dans Boat Voices… L’ampleur de sa culture, internationale, l’originalité de sa vision de la poésie, méritent qu’elle soit connue aussi en France, ce à quoi nous nous appliquerons, en commençant par ce florilège composé de poèmes de Dominique HECQ1https://www.recoursaupoeme.fr/auteurs/dominique-hecq/ (qui a colligé et traduit les textes australiens), Nathan CURNOW 2Nathan Curnow is a lifeguard, poet and spoken word performer. His previous books include The Ghost Poetry Project, RADAR and The Apocalypse Awards. His first collection No Other Life But This was published in 2006 with the help of Judith Rodriguez’s keen eye and invaluable guidance. , Amanda ANASTASI3Amanda Anastasi is an Australian poet whose work has been published as locally as Melbourne’s Artist Lane walls to The Massachusetts Review. Her collections are ‘2012 and other poems’ and ‘The Silences’ with Robbie Coburn (Eaglemont Press, 2016). She is a 2018 recipient of the Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship., Alex SKOVRON 4Alex Skovron is the author of six poetry collections, a prose novella and a book of short stories, The Man who Took to his Bed (2017). His latest volume of poetry, Towards the Equator: New & Selected Poems (2014), was shortlisted in the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards. He lives in Melbourne., et sa traductrice.

Judith Rodriguez au musée Chagall de Nice, 2016 ©photo mbp

Les Etoiles d’Utelle

Marilyne Bertoncini

pour Judith Rodriguez

Hier je l’ignorais encore

mais c’est dans tes yeux que j’ai vu

pour la première fois

les étoiles d’Utelle5* Dans les Alpes Maritimes, la chapelle de la Madonne d’Utelle, fondée vers l’an 850 par des pêcheurs espagnols, sauvés du naufrage par une étoile, aperçue dans la nuit et la tempête au sommet de la montagne, est un sanctuaire et lieu de pélerinage. On y trouve des fossiles de crinoïdes, en forme de minuscules étoiles à 5 branches, que la tradition considère comme des dons nocturnes de la Vierge.

En les cherchant dans la poussière

Je l’ignorais encore

Mais c’était toi que je cherchais

Comme autrefois mes Antipodes

Frêles fossiles au creux des mains

Ces étoiles minuscules

sont ta main d’ombre que je tiens

Par-delà toutes les distances

C’est ta voix d’ombre dans le vent

Qui balaie le plateau d’Utelle

Et la chevelure des pins

Et la mer aperçue au loin

Je pense aux naufragés du Palapa6Judith Rodriguez est l’auteure d’une série de poèmes – Boat voices (en cours de traduction – publiés dans l’édition originale de The Feather Boy, éd. Puncher & Wattmann ) : elle y évoque le drame des réfugiés, refoulés des côtes australiennes – qui fait écho à bien d’autres drames, passés et présents.

the shoal shining, eyes

beyond the margin’s predictable lives

Auxquels tu as donné ta voix

Comme à tant d’autres autour de toi

Ici c’est un naufrage aussi

Qui bâtit la chapelle

Où la Madone rendit sa voix

A la Demoiselle de Sospel

Et ces étoiles du fond des mers

Et des milliers de millénaires

Retrouvent ici dans la lumière

Leurs sœurs célestes qui pétillent

Dans le velours des nuits où brille

le souvenir de tes yeux noirs.

The Stars of Utelle

for Judith Rodriguez

I didn’t know it at that time

but that’s in your eyes I had seen

for the very first time

the stars of Utelle7in Utelle, in the south of France, tiny fossils are found near a chapel, built after mariners had survived a shipwreck, and thought for centuries to be miraculous gifts from the Virgin.

Searching for them in the dust

I still didn’t know it

but it was you I was searching for

as I did once my Antipodes

Frail fossils in my hands

these tiny stars

are your shadow hand in mine

beyond any distance

And your shadow voice’s in the wind

sweeping the highs of Utelle

the hairy pines

and the sea in the distance

I remember the shipwrecked of the Palapa

the shoal shining, eyes

beyond the margin’s predictable lives

to whom you had given your voice

as you did to many around you

Here a shipwreck similarly

built this chapel

where the Virgin gave her voice back

to the Damigel of Sospel

And these stars from the deepest sea

and from thousands of thousand years

meet back here in the light

their celestial glittering sisters

in the velvety nights where shines also

the memory of your black eyes.

©photo mbp

A Voice

Dominique Hecq

For Judith

Says nothing and everything where silence originates

Moonlight catches your shadow

walking closer to streams of dark

rivulets of light about to gel, broken winglets

ankle your shape

I ease my way into the night

all ears, grief a dummy stopping my mouth

And what do you write, you ask in another time

Apricots hang from your friend’s tree

we argue about things poetical, political, heretical, fall

in a heap of white wine giggles

Apricots are little moons at dawn

we argue about the shape of words and sounds

most of all their libidinal, even illicit power

You chide me for using jargon

Thirty years later, I make apricot jam

poeming as I inhale the fruit’s aroma

I laugh at my affectation, a nod

in your direction

say nothing

everything, caught in echoes of your voice

Une voix

Pour Judith

Ne dit rien et dit tout au point d’origine du silence

Le clair de lune attrape ton ombre

qui se rapproche du ruissellement d’ombres

sources de lumière sur le point de gélifier, des ailettes cassées

assaillent ta silhouette aux chevilles

Je m’installe dans la nuit

oreilles pointées, le chagrin une tétine me clouant la bouche

Des abricots pendillent de l’arbre chez ton amie

nous débattons de choses poétiques, politiques, hérétiques, éclatons

d’un rire arrosé de vin blanc

Les abricots sont des petites lunes à l’aube

nous débattons de la forme des mots, de leurs sonorités

surtout de leur pouvoir libidinal, si pas illicite

Tu me reproches l’emploi de jargon

Trente ans plus tard, je fais de la confiture d’abricots

poèmant tout en respirant l’arôme des fruits

Je ris de mon affectation, un hochement de tête

vers toi

ne dis rien

dis tout, prise dans les échos de ta voix

*

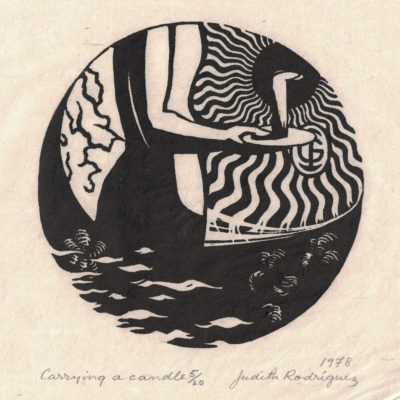

Now

Nathan Curnow8Nathan Curnow is a lifeguard, poet and spoken word performer. His previous books include The Ghost Poetry Project, RADAR and The Apocalypse Awards. His first collection No Other Life But This was published in 2006 with the help of Judith Rodriguez’s keen eye and invaluable guidance.

I know you’re gone

but even now

the dumb surprise of grief

sometimes in a blackout

by candlelight

I’ll enter a room

and catch myself

turning the light switch on

©Judith Rodriguez, Carrying-a-candle-1978

Maintenant

Je sais que tu es partie

mais même maintenant

la sidération du chagrin

comme lors d’une panne d’électricité

avec une chandelle

entrer dans une pièce

et se surprendre

à vouloir allumer une lampe allumée

*

Poets

Amanda Anastasi9Amanda Anastasi is an Australian poet whose work has been published as locally as Melbourne’s Artist Lane walls to The Massachusetts Review. Her collections are ‘2012 and other poems’ and ‘The Silences’ with Robbie Coburn (Eaglemont Press, 2016). She is a 2018 recipient of the Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship.

We run our fingers

over the shell of humanity

feeling for the pulse of its mettle,

the rhythms of its prejudices,

the beat of its concord;

drunk on the beautiful, redefining

its boundaries — its height, its breadth,

its colours; worshipping a horizon’s

sweep and the vein of a leaf,

the collected light of a city

and the glisten in an eye;

capturing a moment

in the universe

and the universe

in a moment.

Poètes

Nous passons le doigt

sur la coque de l’humanité

prenant le pouls de son courage,

les rythmes de ses préjugés,

la mesure de son harmonie;

saoulés de beauté – sa grandeur, sa largesse,

ses couleurs; adorant l’arc

d’un horizon et la veine d’une feuille,

la lumière réfractée d’une ville

et l’éclat d’un regard;

capturant un instant

dans l’univers

et l’univers

dans un instant.

*

Crossing

Alex Skovron10Alex Skovron is the author of six poetry collections, a prose novella and a book of short stories, The Man who Took to his Bed (2017). His latest volume of poetry, Towards the Equator: New & Selected Poems (2014), was shortlisted in the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards. He lives in Melbourne.

for Judith Rodriguez

They are tramping past my house,

I can see them out the corner of my eye,

the one I keep open when the sunlight dazzles.

They barely glance in my direction

as they follow at a steady, deliberate pace,

crossing the street while impatient traffic idles.

I’ve seen them many times, many places,

yet always they appear the same: weary, guarded

or discomposed, striding on regardless.

What do they harbour in those backpacks,

those cardboard suitcases, their corners battered,

faded labels half-torn or peeling?

Where do they trudge to, their knuckles clasped

around bony handles, or clutching

the lapels of shabby overcoats?

If one of them should uplift a weathered brow

and turn to glimpse the window I inhabit,

she swiftly looks away, in reprimand.

This morning, squinting against the sun,

I ventured out, thinking I might confront them:

they walked right past, as if I wasn’t there.

I ran inside to hide among mirrors and folders,

waiting for their footsteps to recede,

unsettled by the certainty of their return.

Traverse

pour Judith Rodriguez

Ils dépassent ma maison d’un pas lourd,

je les vois tous et toutes du coin de l’oeil,

celui que je garde ouvert contre le soleil éblouissant.

C’est à peine s’ils m’adressent un regard

lorsque d’un pas mesuré et délibéré ils

traversent la rue, le trafic impatient au ralenti.

Je les ai souvent vus, un peu partout,

toujours semblables à eux-mêmes: las, furtifs

ou décomposés, allant de l’avant, imperturbables.

Mais que recèlent-ils donc dans ces sacs à dos,

ces valises de carton aux coins cabossés,

étiquettes estompées, mi-déchirées ou pelées?

Mais où se traînent-ils donc, phalanges serrées

sur de maigres poignets, ou agrippées

aux revers de manteaux râpés?

Si l’une d’entre eux lève son front ridé

balayant des yeux la fenêtre où j’habite,

elle s’empresse de détourner le regard.

Ce matin, les yeux plissés contre le soleil,

je suis sorti, avec l’intention de les aborder:

ils ont poursuivi leur chemin, comme si je n’existais pas.

J’ai filé me cacher dans mes miroirs et mes classeurs,

attendant que leurs pas s’amenuisent,

ébranlé par la certitude de leur retour.

*

©photo mbp

Sur le balcon que tu aimais

Marilyne Bertoncini

pour Judith

Sur le balcon que tu aimais

nous tenons allumée une petite flamme, afin qu’elle t’accompagne dans le froid de ton

long voyage infiniment nocturne

vers les étoiles.

Le jour, c’est un petit clou trouant la pénombre presque phosphorescente de la fougère arborescente.

Le soir, sa couleur chaude irradie d’or et de turquoise le front assombri de la plante de Tasmanie.

Ce midi, une fauvette est venue visiter les feuilles dentelées de la fougère des antipodes –

peut-être ne l’aurions-nous pas vue si, voletant autour de la flamme, son ombre dansante n’avait attiré notre regard.

Elle a sauté de feuille en feuille, jusqu’à la crosse la plus jeune,

puis a disparu dans l’azur,

de l’autre côté du balcon,

dans l’infini de l’outre-monde.

On the balcony you loved

traduction de l’autrice

for Judith

On the balcony you loved

we lit the flame of a candle, to keep you company in the cold of your long and dark endless voyage

towards the stars.

By day, it’s just a nail piercing the phosporescent shadow of the tree fern.

By evening, its warm color radiates gold and turquoise on the darker forehead of the Tasmanian plant.

At midday, a warbler visited the indented leaves of the fern from the Antipodes –

we might not have seen it if, fluttering around the flame, its dancing shadow hadn’t caught our attention.

It sprung from leaf to leaf, up to the youngest fiddlehead green,

then disappeared in the deep blue,

the other side of the balcony,

in the infinity of the outer-world.

*

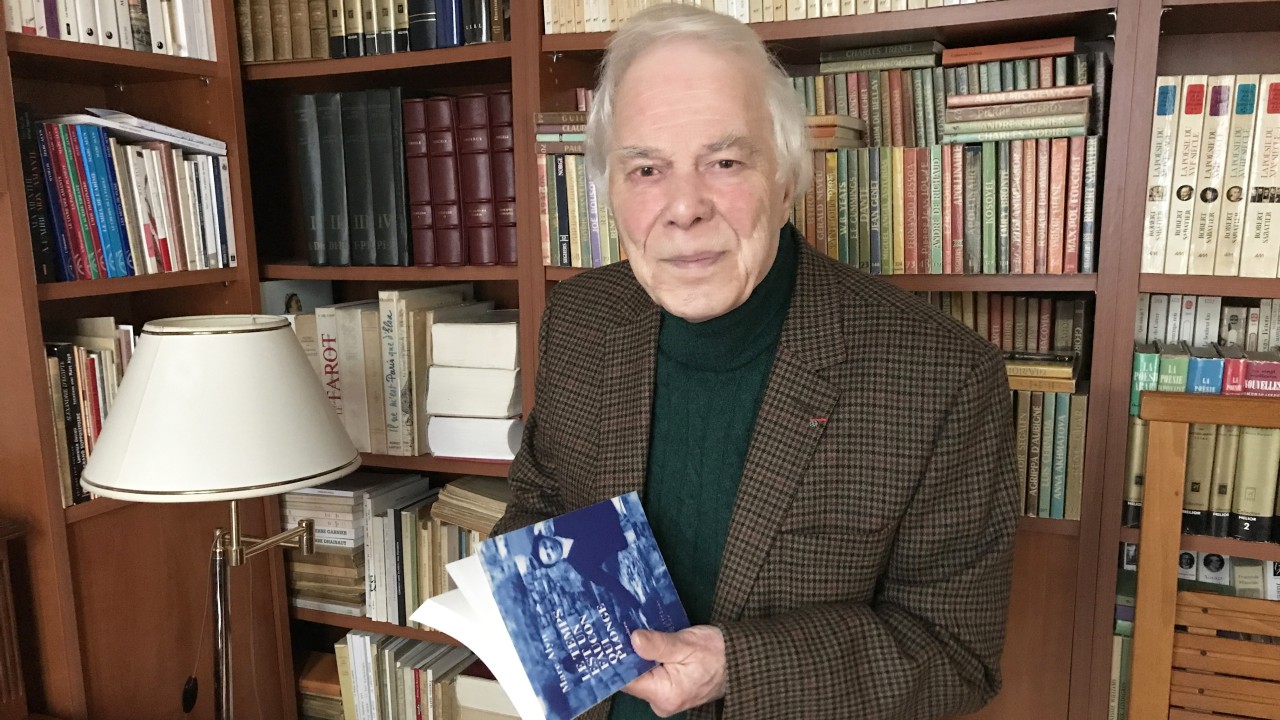

A Tribute to Judith Rodriguez

By Amanda Anastasi

It is with much sadness, fondness and celebration that we recognise the passing of our poet and friend, Judith Rodriguez. She leaves behind a legacy of prolific and memorable poems. Her poetry collections include (among many others) Water Life, Shadow on Glass, Mudcrab at Gambaro’s, Witch Heart, The Hanging of Minnie Thwaits and (shortly before her death) The Feather Boy and other poems. She was the poetry editor of Meanjin for a time and also for Penguin Australia, and a recipient of the OAM for services to literature, in addition to many other honours. As well as her extensive literary achievements, she was a social justice campaigner and advocate and was involved with PEN International across three decades, fighting for freedom of expression and promoting intellectual cooperation between writers globally.

As a teacher, Judith taught writing at the CAE and previously at Latrobe University and also at Deakin University for 14 years. This was where I came in contact with her, as a first-year Professional Writing and Editing student. I still recall her insistence that all students keep a writing journal to jot down our daily thoughts, ideas and musings. I remember entering Judith’s office as a nervous 18-year-old for the end-of-semester journal showing, which she said would be a brief check to see that we were maintaining our daily writings. Upon handing my notebook to her, she proceeded to intensely read it from cover to cover over a period of 15 minutes while I stood there watching. I remembered thinking “why does she – why would she — find my thoughts and notations of interest?” It was my first glimpse of the lady’s curious mind and deep interest in other people’s thoughts and ideas. Many, many years later I encountered her again on the Melbourne poetry scene. Upon asking her to look over my first poetry collection ‘2012 and other poems’ (expecting a polite no), she gladly and readily obliged and her written testimonial graces the back cover of both editions.

Judith was not merely a teacher, she was a mentor and a supporter of emerging poets throughout her life. She saw the potential in everyone, no matter their writing style or level of ability. This poetry caper was never just about her. Rather, it was concerned with a larger, collective practice of poetry, artistic expression and craftmanship. She was a person who was confident in her abilities and doggedly focused, though without the egotism. Her natural, deep interest in the world around her preserved that humility, hands-on helpfulness and down-to-earth humour that was so very particular to her. Judith was a listener and a creative enabler. She fully utilised her time onstage and the various platforms she had been given, but viewed the platform as a thing to be shared.

Judith’s poetic output was above and beyond any label that one could possibly place on it. One wouldn’t even think of calling her “a female poet” but, rather, an “Australian poet” or “a poet”. She was simply one of our greatest wordsmiths and teachers of poetry, and a respected academic and vocal human rights activist. Her mastery of words and stoical objective to preserve free speech and diverse voices made her universally respected. What she left behind in the poems and the poets she taught means that she will be always with us. Myself and so many others who came into contact with Judith will hold the memory of her in our hearts always, as a great example of what and how we could someday be.

Hommage à Judith Rodriguez

C’est avec beaucoup de tristesse, d’amitié et de révérence que nous assumons le décès de Judith Rodriguez, chère poète et amie. Elle nous lègue un héritage de poèmes à la fois prolifique et mémorable. Parmi ses nombreux receuils de poésie, nous retenons Water Life, Shadow on Glass, Mudcrab at Gambaro’s, Witch Heart, The Hanging of Minnie Thwaits et (peu avant sa mort) The Feather Boy and other poems. Elle fut éditeur chez Meanjin et aussi, brièvement, chez Penguin Australia. Elle fut aussi récipiendaire de la médaille d’honeur de l’Ordre d’Australie pour services rendus à la literature. En plus de ses accomplissements littéraires, elle milita avec ardeur pour la justice sociale dans le cadre de PEN International durant trois décennies, défendant férocement la liberté d’expression et encourageant la coopération intellectuelle entre écrivains à l’échelle globale.

En tant qu’enseignante, Judith exerça au Conseil d’éducation pour adultes (CAE) ainsi qu’à La Trobe University et Deakin University, où elle enseigna pendant quatorze ans. C’est là que je l’ai rencontrée quand j’étais étudiante en première année dans la section Ecriture Professionnelle et Edition. Je me souviens encore combine elle exigeait que nous prenions note de nos menues pensées, idées et réflexions quotidiennement dans un journal. Je me souviens lui avoir montré mon journal en fin de semestre cette année là pour qu’elle vérifie que j’avais respecté la consigne. J’avais dix-huit ans et j’étais nerveuse. Elle a pris mon journal et elle s’et immédiatement plongée dedans. Il lui a fallu quinze minutes pour couvrir le tout. Je la regardais et je me souviens m’être demandé pourquoi trouve-t-elle –pourquoi trouverait-elle –mes pensées et mes annotations intéressantes. C’était la première fois que je voyais à l’oeuvre l’esprit bizarre de la femme et l’intérêt qu’elle portait à autrui. Bien plus tard, je l’ai revue sur la scène de poésie à Melbourne. Lorsque je lui ai demandé si elle voulait bien lire mon premier receuil, 2012 et autre poèmes (m’attendant à une réponse negative), elle s’est empressée d’accepter. Elle a même rédigé une note de lecture pour la quatrième de couverture.

Judith n’était pas seulement une enseignante, elle prenait son rôle de mentor auprès de jeunes poètes très au sérieux, et cela tout au long de sa vie. Elle percevait un potentiel chez chacun de nous indépendemment du style et de la qualité de l’écriture. Ces cabrioles poétiques ne concernaient pas seulement sa personne. Elles témoignaient plutôt d’un désir de faire de la poésie une activité collective dont la raison première et fondamentale était l’intégrité artistique. Elle était quelqu’un qui avait confiance en ses capacités et elle avait une grande faculté de concentration; certes, sans l’égotisme. Une profonde curiosité envers le monde qui l’entourait préserva son humilité, serviabilité et son humour pragmatique si particulier. Judith avait le don d’écouter et d’encourager la créativité. Elle utilisait pleinement le temps qui lui était octroyé sur scène, mais elle considérait la scène comme une plate-forme à partager.

L’oeuvre poétique de Judith est imperméable à toute etiquette dont on voudrait l’affubler. Il serait même impensable de l’appeler ‘une femme poète’, mais bien au contraire, ‘un poète Australien’ ou ‘un poète’. Elle était tout simplement l’un de nos meilleurs wordsmiths, professeurs de poésie, universitaires respectés et activistes pour les droits de l’homme. Sa maîtrise de la langue et son objectif stoique de préserver la liberté d’expression lui ont valu un respect universel. Ce qu’elle a transmis dans ses poèmes et aux poétes qu’elle a formés signifie qu’elle restera toujours parmi nous. Comme tant d’autres poètes qui ont connu Judith, je garderai son souvenir dans mon Coeur en guise d’exemple de ce que nour pourrions un jour devenir.

*

Notes